The most suspicious thing I've ever seen on YouTube

The curious case of Benny Johnson's channel

I’ve been publishing political content to YouTube for a long time (see my 2009 videos, which make me cringe). One of the tried and true realities of publishing to YouTube for many years is that you come to realize there are some inevitabilities. These include that video performance can be unpredictable, that if you publish political content, roughly half of your audience will hate you and your content, and, relevant for us today, that new subscribers follow video view numbers extremely closely, except when something odd or unusual is taking place.

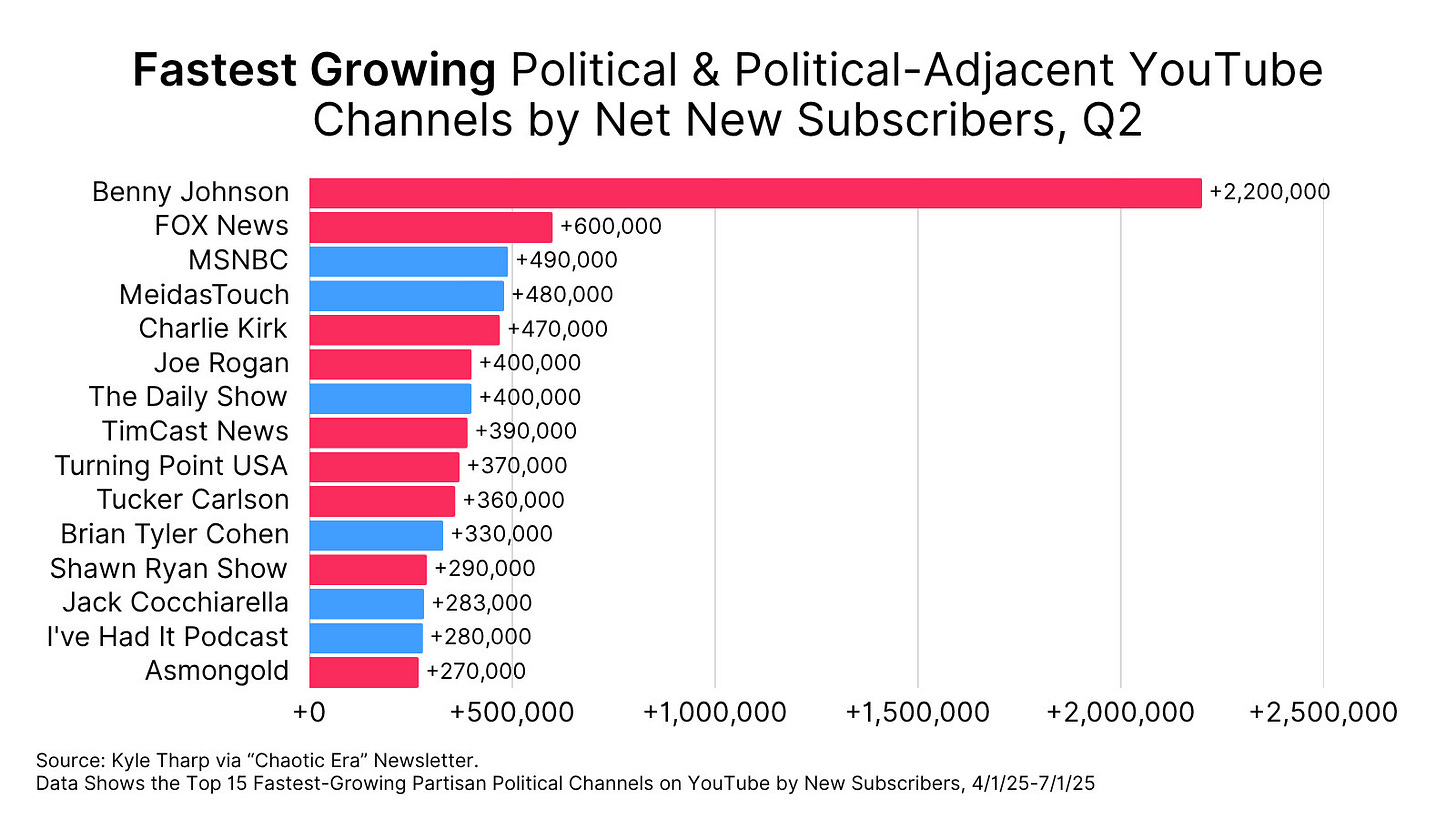

This week, writer and researcher Kyle Tharp published a piece called “This right-wing YouTuber is having a moment.” The most important and unusual takeaway from this piece is that right-wing content creator Benny Johnson’s channel was the fastest growing politics or politics-adjacent channel in Q2 of 2025 by a long shot, gaining 2.2 million subscribers in April, May and June of this year:

Why is this unusual? Because Johnson’s new subscriber numbers are completely out of line with views, which tend to move in parallel.

Before going further, I should acknowledge that the reason to be suspicious of what’s happening on Johnson’s channel is that he has a track record of not exactly being on the up-and-up. Johnson was one of the content creators caught up in the 2024 scandal in which it was revealed that he was indirectly receiving Russian money through an American company called Tenet. Johnson and others have argued that they had no idea the provenance of the funds was Russian, but these claims raise eyebrows as the payment rates far exceeded the market rate. In some cases, fees were as high as $400,000 per month, sometimes including six-figure signing bonuses.

If you aren’t already a subscriber of this Substack, become a subscriber now.

Back to our subscriber-to-view observations, with few exceptions (which I will detail momentarily), YouTube views drive subscribers. More popular videos drive more subscribers, and the ratio is quite predictable over time.

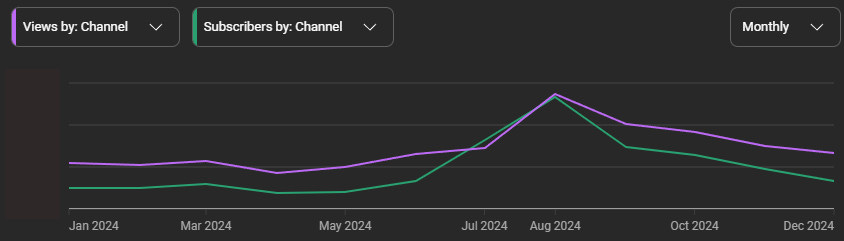

Looking at analytics from my channel (3.27 million subscribers as of this writing), where the purple line represents views and the green line represents net new subscribers, one can immediately see the pattern: More views, more subscribers (data from my own YouTube analytics):

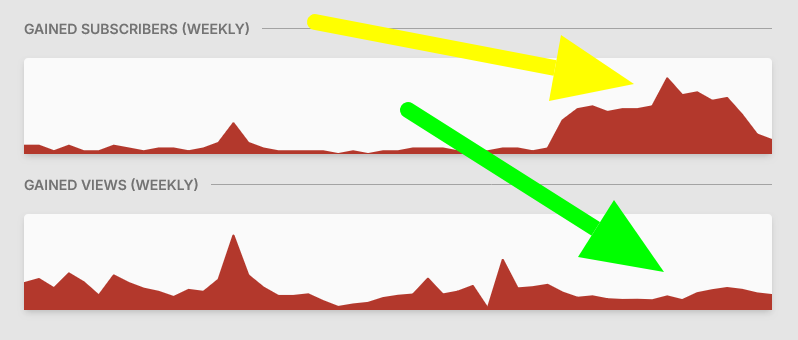

The curious reality is that during Q2 of this year, Johnson’s subscribers have exploded, but views have not. Check out the side-by-side comparison (data and charts from Socialblade.com):

These charts go back about a year, but the key areas, Q2 of this year, are under the yellow and green arrows. As you can see, explosive, unprecedented subscriber growth, with no view growth (and possible even stagnating views).

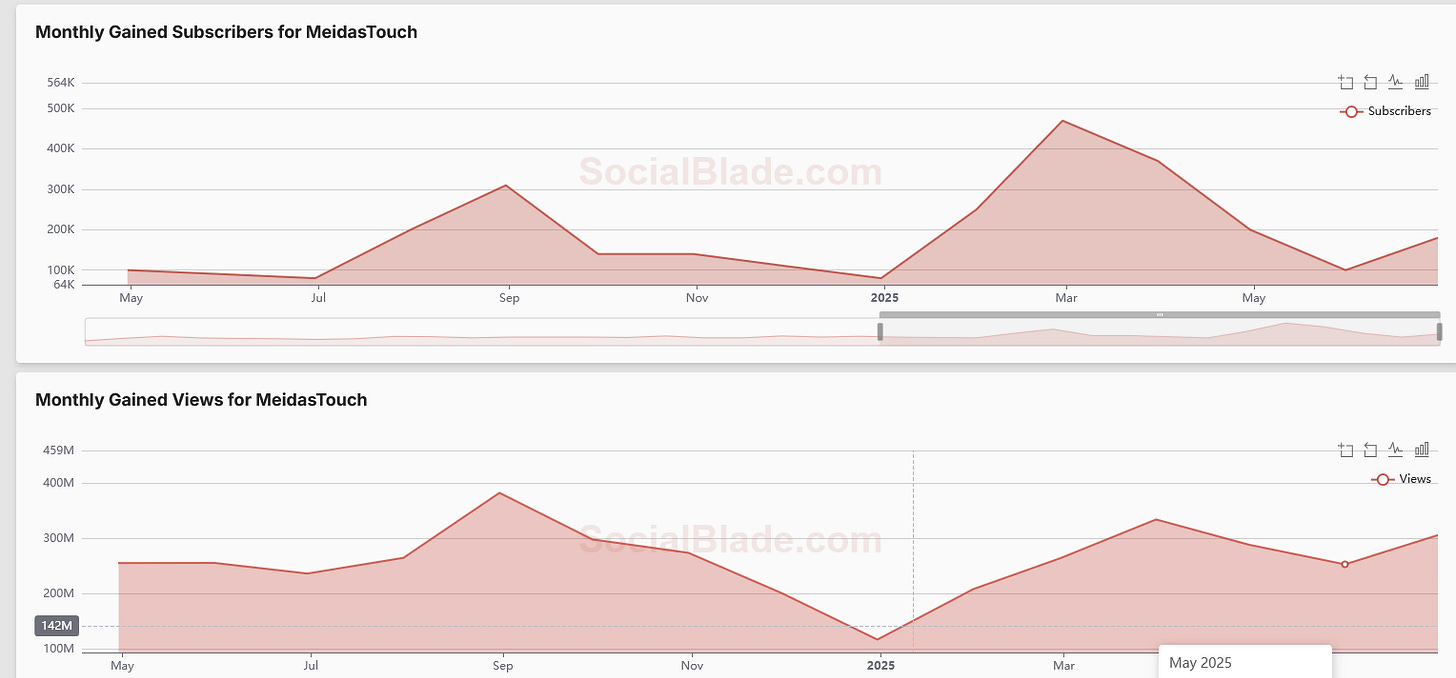

For comparison, MeidasTouch, the fastest growing independent progressive YouTube channel, also featured on the list, has a similar number of total subscribers (5.2 million versus Johnson’s 5.4 million) but actually generates views proportional to subscriber numbers (data and charts from Socialblade.com):

Notice how with MeidasTouch, high subscribers and high views are happening at the same time. This is expected, logical, and coherent.

So what’s going on here?

There are only a few scenarios that can cause view and subscriber numbers to stop tracking each other.

If a creator says something on their channel so vile, so disgusting, so offputting, that it causes mass unsubscriptions, one can see unsubscribes significantly exceed views, because as views for that video go up, people are so disgusted that they click unsubscribe and this causes a lack of parity between the two metrics. This tends to only work in reverse, because a popular video that people like the content of would have high views and high new subscribers, which is the normal pattern.

Artificial subscription sources

This second category is broad, to be clear. For example, one can accelerate subscriptions above where views would track by paid subscriber acquisition, which is completely legal, though rarely used by political creators due to cost inefficiency and targeting issues. Paid subscriber acquisition typically involves running YouTube or Google ads that encourage users to subscribe to your channel.

These campaigns can work, but they usually require significant budget and are more often used by lifestyle or product-based channels that directly monetize subscribers through merchandise or sponsored content. For a political content creator like Johnson, using paid acquisition to this extent would be atypical—especially in the absence of a clear monetization model that justifies the expense.

However, if third parties are doing it on your behalf, the financial logic changes. A super PAC, foreign influence operation, or deep-pocketed ally might see value in artificially inflating a creator’s subscriber count to boost perceived influence or algorithmic reach. In that context, the normal cost-benefit analysis takes a backseat to political objectives.

Another possibility is embedded auto-subscribes. In rare cases, creators have used technical tricks—like embedding subscribe actions in pop-ups, redirects, or external sites—to artificially inflate subscriber counts. These tactics violate YouTube’s terms of service and are usually cracked down on quickly when detected.

Then there’s cross-promotion—when a creator is boosted by a larger channel or network, which drives subscriptions out of proportion to views on the original channel. This can happen when a channel is featured in newsletters, email blasts, or inside other content ecosystems. But this tends to drive both views and subscriptions — not subscriptions alone — unless the promo is happening somewhere that encourages subscribing directly without viewing.

Finally, the most concerning explanation: subscriber farming. There’s an underground market for buying YouTube subscribers through third-party vendors who deploy clickfarms or use compromised accounts. These sorts of operations—particularly when carried out by third parties to inflate metrics, distort perception, or manipulate platform algorithms—are ideologically and technically similar to the kinds of influence campaigns run by Russian propaganda entities, such as the Internet Research Agency. The goal is often the same: shape public opinion not through persuasion, but through artificial amplification.

These subscribers are usually low-quality and may eventually be purged by YouTube’s audits. But in the short term, they can give the illusion of popularity and influence. If your goal is to land press coverage, brand deals, or political clout, that illusion can be valuable.

What is Benny Johnson doing?

I enumerate these possibilities without evidence that Benny Johnson’s channel is benefiting from any of these techniques. What I do know, from more than 15 years on YouTube, is that such a noticeable spike in subscribers is atypical and illogical without a corresponding rise in views. I have never experienced it in these more than 15 years, and no other content creators I spoke to have either.

While the explanation currently eludes us, the implications, depending on what is going on, have massive implications in the YouTube space and in the broader alternative and online media ecosystem.

If it’s a coordinated third-party campaign to boost a creator’s visibility, it raises questions about how influence operations are manipulating platform metrics to manufacture credibility and shape political discourse. This would echo previous election interference strategies but through a new, subtler lens.

If it's an algorithmic vulnerability being exploited, like a loophole in how subscriptions are recommended or recorded, it suggests that YouTube’s integrity mechanisms may be more fragile than assumed. That would impact everyone by skewing discovery and recommendation systems.

If paid subscriber acquisition is being used at scale for political ends, even legally, it would mark a shift toward a kind of “influence laundering,” where perception of popularity becomes as valuable as actual engagement. This could prompt an arms race of artificial growth, warping the playing field for smaller or less-funded voices.

If it turns out to be fraudulent, like bots or purchased subscribers, it exposes both the ease of gaming the platform and the lack of effective enforcement. And if that manipulation helps secure media coverage, fundraising, or even political capital, the downstream effects extend far beyond YouTube.

What do you think is going on? Leave a comment! And please share this article on social media.

Paid memberships make articles like this possible. Your support helps cover the time, research, and work that go into each piece. If you find value in what you’re reading, consider becoming a paid Substack subscriber—it keeps this work going.

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck.........

I vote for Russian influence again. No proof. Just track record.